Israel’s systematic destruction of educational institutions and infrastructure, and deliberate targeting of scholars and academics in Gaza, is increasingly being recognised around the world as a practice of scholasticide (with some preferring to speak of “educide” or “epistemicide”). Like the ethnic cleansing and genocidal violence that we have witnessed since October 2023, this phenomenon is rooted in a decades-long war on Palestinian culture by the Israeli state. From your vantage point as a scholar and educator in Palestine, what is your understanding and analysis of scholasticide, both in its long history and in its current manifestation?

From the Zionist perspective, the targeting of educational institutions is a destruction of Palestinian institutions as part of the process of uprooting all that which is Palestinian. In this regard, the university could be seen to be as Palestinian as the olive tree and the mosque or church, which must be destroyed and wiped away.

So, the targeting of educational institutions is a targeting of yet another aspect of the Palestinian existence, one more root to be pulled out. It can also be seen as an attempt at emptying out the Palestinian, a targeting of knowledge, another attempt to reduce Palestinians into bare existence; it is an uprooting of the human from the Palestinian, the human as both a biological and intellectual being. A realization of the claim that the Palestinian is a ‘human animal,’ and in this case, the human refers merely to the species in the barest form of its life: an existence that is deprived of its biological needs, and of any ability to develop the means through which these can be met.

From another perspective, the targeting of Palestinian education and culture is an enactment of death. Not the death that is part of life but death that stands for a void, a vacuum that the Zionist project has always claimed exists in the land it now colonizes, a vacuum that the Jewish settler is supposed to fill. In this sense, the destruction of educational institutions is the uprooting of knowledge of that which is Palestinian but also of any Palestinian knowledge; it is also an uprooting of memory, the memory of the past, as well as the memory of the present in the future. It is thus an uprooting of the Palestinians in their past, present and future.

We can see this destruction of cultural institutions as a war on Palestinian culture, but culture is not something static, not a mere monument that can be dismantled or burnt down, culture is a product of human existence of human work, intellectual and physical, and as long as the human lives then culture lives even if in changed forms. I do not underestimate the importance of cultural symbols and monuments in the making of the identity of a collectivity, but neither culture nor identity can be reduced to a monumental status, they too change with every battle the Palestinian has to undertake with Zionism. In the end, it is the Palestinian fighting and resisting who gives life to his culture and identity, and not some reified notion of culture and identity that grants the Palestinians their existence.

There is another thing involved in the destruction of educational institutions, since the Nakba, when the Palestinians were uprooted from their villages and cities. Education became one major way of resistance. Palestinians thought of education as a process of re-rooting themselves, of regaining power. In this case, knowledge as power was not the knowledge of domination, but rather knowledge as means of asserting presence on the land and in the world; it has been a means for survival and combat. An infinite source from which the Palestinians maintain their existence, after every war of destruction that the Zionist entity carries against them. Academic institutions have been part of how Palestinians find ways to confront and resist colonial dispossession and colonial annihilation, they have been a means for reclaiming the land, for creating new means of survival. I am talking here about the knowledge that allows the Palestinians to create the means of defending themselves, of maintaining their lives or building new ones, many times from scratch. In the case of Gaza, educational institutions have been part of creating self sufficiency, when the whole world became complicit in the slow annihilation of Gaza and its Palestinians through isolation and blockade.

Academic institutions are important, they are a major constituent part of what makes the Palestinian collective, the knowledge they produce goes in direct and indirect ways into combatting colonial domination. But knowledge was never and can never be confined to the academic institution, when knowledge just as food is a necessity for survival then people will always find ways of knowing and in different forms, they will also find ways to maintain their collective existence, it is a matter of will, a deep-rooted will just like that of survival. So while the Zionist, like other colonizers throughout history, attempt to find their domination in the destruction of the knowledge of others, in destroying their history, past and present, we have to remember that these do not only exist in books or archives , we carry them in our bodies, and while our bodies are also the main targets, what we carry in them remains collective and is passed from one generation to another. So, the Zionists will have to wipe away every single Palestinian to have the knowledge of Palestine wiped away, they will also have to wipe away the destruction and erasure itself, for every destruction leaves behind traces from which what is destroyed can rise and grow back.

Palestinian universities have been fulcrums of resistance while also being targets not just of repression but also of capture and broader processes of domestication and ‘NGOization’. How do you view the current relationship between academic life and Palestinian liberation in the shadow of an increasingly brutal occupation regime, ethnic cleansing, and genocide in Gaza?

The question of domestication and NGOisation of universities is the question of neoliberal and neocolonial forms of power. These are processes that connect Palestine to other places experiencing these same processes. But in the case of Palestine, knowledge cannot be reduced to a means for market access. And we know knowledge is now reduced to its technical instrumental aspects worldwide. But for a people fighting for their existence, a people in a struggle for life and liberty, this instrumentalization of knowledge can have very negative repercussions, including the emptying out of the university campus, the atomization of the student body, and the depoliticization of student/university life, which in Palestine as in the other contexts has been at the core of liberation and anti-capitalist revolutionary struggles.

So here too we see that dismantling of the collective body, and the removal of the political from the daily experience of students. This applies to the link that has always existed between knowledge, political revolt and liberation struggles, where the student, treated as the potential homo economicus is to be given the correct doses and kinds of knowledge that enables the realization of this potential, while at the same time inhibiting other potentials for the human being in general. In the case of the Palestinian this means hindering educational institutions from being spaces for knowledge gaining as a collective political experience that might enable a transformation of systems of domination, including the colonial and imperial ones seeking to annihilate the Palestinian.

This does not mean that Palestinian universities are emptied out completely of politics. This is not really possible in a context of daily colonial oppression: colonialism, unlike neoliberal forms of domination, is a visible external power that cannot be internalized as both Marx and Fanon had it; the contradictions it creates remain visible and thus even if the political at certain instances withdraws, it comes back to the fore, for as long as there is occupation there will be resistance. We thus can say that while liberal transformations are taking place in Palestinian universities, they still have to take place in a context where colonial and anti-colonial confrontations are persistent. So, in a Palestinian campus you get both political attachment and detachment at the same time. And the work of neoliberalism, of depoliticization and atomization in Palestinian universities as in the Palestinian society is never complete.

Palestinian universities, as well as civil society more broadly, were crucial to the launching of the Boycott Divestment and Sanctions movement as the most prominent and contested vehicle for international solidarity with Palestinian struggles against occupation, settler colonialism and ethnic cleansing. What is your judgment about the state and prospects of international solidarity? In particular, how do you see the role of academics and universities internationally in supporting Palestinian struggles? What do you think are the shortcoming or limitations of academic solidarity, and how could it be refined or amplified?

University students and faculty in different Western countries have been organizing and demonstrating against the war on Gaza and calling for ceasefire, with many of them facing arrests, threats and other kinds of harassment, mainly in the US and Britain, which aims at deterring them from speaking/acting for Palestine. And many have shown a lot of courage in their willingness to take different risks involved in speaking and acting for Palestine. Many have shown commitment and a principled sense of solidarity.

When it comes to BDS, as other acts of solidarity, it has been at many instances disruptive and sometimes sabotaging of certain forms of global support for the Zionist state.

I think that solidarity work has a stronger impact when it is not seeking merely to allow a place for Palestine in the existing world, without problematizing that world. When that happens, one is overlooking something that is becoming clearer every single day, which is that Palestine is the persistent questioning of modernity, of a capitalist and imperial world. If Marx thought that the Jewish Question in Germany was the question of capitalism, then the Question of Palestine is the question of an imperial world, of the world division of labor, of imperial as well as colonial plundering, exploitation, uprooting and mass murder. So, for me to be in solidarity with Palestine is not to demand that Palestinians be recognized by the international community, or that international law applies to them as well, but to liberate oneself from the limits imposed by such entities on our ability as peoples to question this world, including its security and legal entities. Solidarity for me is thus enacted and practiced in every revolutionary act in any country and by any group of people aiming at combatting imperialism, not as an abstract idea, but in its different and multiple materializations.

When I think of solidarity, I usually think of it in the form of links, of unearthing and making visible those links that connect the peoples of the world together. I am thinking of deeper solidarities, not necessarily ones based on common forms of oppression and common struggles, but rather, or maybe also, ones that are based on different positionalities that are, despite their differences, in contradiction with the existing world order. It would be real solidarity when the Egyptians revolt against hunger and their increasing sinking into debt. It would be solidarity when Black people fight the racism that turns them into disposable subjects, to be shot in the streets, incarcerated in prisons or sent to fight White America’s wars; when people in the United States or in Canada fight for other modes of life that do not entail the destruction, expropriation and exhaustion of what remains of human and natural resources, when wealth and money are questioned as the main reasons for our existence as humans – that would actually go directly to addressing what is happening now in Gaza, as in Sudan, Congo, and Haiti, in Venezuela, as well as in Armenia.

As for the roles of universities and academic institutions, I think their role can be in questioning their positionality in the world capitalist machine, in trying to break free from processes of circulation, in the mechanisms of publishing or in the politics of academic conferences, for example. We can always make use of Walter Benjamin’s counsel, that to be anti-capitalist is to question and problematize one’s position within the capitalist mode of production, this can also apply to questioning and problematizing one’s position within the relations and structures of the imperial world.

This does not mean that we just talk or write about colonialism and imperialism within the existing academic institutions; this could be useful but is limited in its ability to impact the current world order. We can try to find ways in which knowledge is no longer another commodity, or a tool for capitalist and imperial domination, but a source of power, a practice of consciousness that is anti-imperialist and anti-colonial. One can start by not merely boycotting Israeli universities for their roles in the production of weapons or in laying knowledge foundations for a settler-colonial project, but by questioning every single academic department, and every single production of knowledge that is put into the service of imperialism and capitalism in different ways, and not only in Israel. What I mean is that we need as academics to start by liberating knowledge, which is also liberating ourselves from the limits and roles given to us in the capitalist academic machine. This is not just about speaking and writing against, but also about speaking and writing for something other and different, which might gain enough power to create a horizon and set bases for a different world.

Notwithstanding global attention, protest and debate elicited by the most recent war on Gaza, the voices, analyses, and theoretical perspectives of Palestinians are largely absent in the ‘global North’, with the limited and partial exception of some intellectuals and academics in the Palestinian diaspora. What do you see as the effects of this silencing or marginalisation? More constructively, in view of your own experience and analysis of the current conjuncture in Israel’s colonial war on the Palestinian people, what do you think are the critical issues that international academics in solidarity with Palestine should attend to? Though historically-informed critiques of Zionism and settler-colonialism have now made inroads into a progressive common sense – while being objects of attack on campuses and in the media – are there dimensions of Israeli state violence and of the reality of resistance that you think have not been properly attended to in international discussion?

As far as I have been able to follow up with solidarity discourses, there has been a tendency to build on how different Palestinian groups, organizations or intellectuals have been framing the Palestinian cause, so there is the discourse about the need to apply international law, and UN security resolution to end the occupation of 1967 occupied lands; there is also the discourse of apartheid, i.e. Israel as an Apartheid state, and now the narrative of anti-Palestinian racism, as well as the recent discourse of indigeneity and the framework of settler-colonialism being applied to the case of Palestine.

For the first two discourses/narratives they seem to be directed by a need ‘to be strategic’, that is, to employ a narrative that can easily (without complicating issues) be put into practice. But simplification of issues, just like other forms of the rational instrumentalization of knowledge, involves a willed blindness, that is, blinding ourselves to why and how international law solving the Palestinian question as one of Occupation or of Apartheid has been failing since before 1948. Of course, the apartheid discourse is much more recent, but still it seeks a solution based on international legitimacy while failing to question the notion and practice of legitimacy as one based on and shaped by power relations, on colonial and imperial power relations – to know that but disavow it for the sake of strategizing is to be strategizing for failure or at least for perpetuating the status quo.

The current battles for ceasefire in Gaza in the UN security council between the world powers attests to that.

As for the discourse of Apartheid and racism, it too is unable to transgress the limits of a legal discourse and legal details, it also runs the risk of turning the colonized Palestinian threatened with uprootedness into a subject of racism, racism here of course reduced to its legal aspects and emptied out of its colonial and exploitative capitalist aspects. Not to mention that it seeks to build on something that the sought-for audience in the West is supposed to be familiar with, but that comes at the expense of collapsing one experience of oppression into another. There is a difference between me saying I can feel with Black people being shot in the street in the US for being Black just as Palestinians are being shot for being Palestinian, and the identification of the two forms of oppression in a legal discourse. I think what connects them more is their urge to go beyond the limits of legality. Solidarity lies in the ability to understand and know what it is to be oppressed; it is knowledge inextricably linked and founded upon feeling, and as such, one cannot force upon people how they should know and identify this oppression – but such a stance will necessarily have to do without the notion of legitimacy.

Regarding the third narrative, the one about indigeneity and settler colonialism. Yes, I agree Israel is a settler-colonial state that seeks to eliminate the people of the land, but eliminate here means for me to uproot, it is not about merely wiping us away as Palestinians but as physical human beings who have roots in this land, and thus need to be uprooted. The other problem with this narrative is twofold, first it overlooks the imperial aspect of the colonization of Palestine, which this war on Gaza is now demonstrating, while it also gives (despite any good intentions) the Israeli state the same legitimacy that other settler-colonial entities were given in the past. Instead, Palestine could be looked at as the place from where what is legitimized through a discourse of settler colonialism (not only in Israel) can be delegitimized as embodying forms of imperialist expansion and plundering and acts of annihilation, to which different peoples are being subjected in different degrees and in different forms, even when these take forms other than that which was defined and standardized as imperialism. In this case, neither Palestinians nor those in solidarity with them will have to look for the most legitimate/strategic narrative to employ to be in support of Palestine but will find many different ways of supporting Palestine by locating the different centers where imperialism can be hit and resisted.

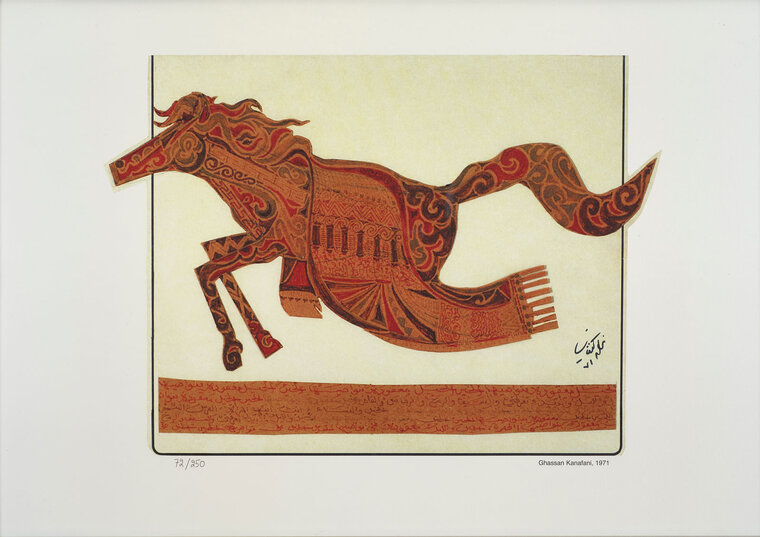

Your own research has focused on the nexus between anti-colonial resistance and anti-colonial literature, with a specific focus on the writings of Aimé Césaire and Ghassan Kanafani. What kind of resources do you find in the poetic and political practices and traditions you’ve studied for thinking in and against the present? Do you have any reflections on how literature has also become a flashpoint in regard to solidarity with Palestine – I am thinking for instance of the cancelling in October of Adania Shibli’s award ceremony for Minor Detail at the Frankfurt Book Fair or of the work carried out by the Palestine Festival of Literature and organizations like Writers Against the War on Gaza.

I have engaged in writing and teaching with the works of all three writers (Césaire, Kanafani and Shibli) as examples of rebellious texts; I do not consider them narratives or discourses, they are texts that do not seek recognition, nor can they be ideologically identified. They make their case without seeking to make a case. What I mean is that their rebelliousness or revolutionary aspects lie exactly in their refusal to establish the legitimate and recognizable colonized subject. Kanafani and Césaire do not write about colonial oppression, their writings rather are their way of confronting and rejecting the position of the oppressed and colonized. They write anti-colonial struggles and resistance, every poem and story is a cry that mobilizes anger, pride and a rejection of a life of helplessness and humiliation.

In Shibli’s work, freedom lies in the silence, in the refusal of the colonized to give the intelligible voice, a narrative that can be recognized and comprehended; the only intelligible voice in Shibli’s text is that of the colonizer, and what is questioned and problematized are those who seek the voice of the murdered colonized from the past, while blinding themselves to the present and continuous acts of colonialism. It is thus the world’s blindess and silence that is condemned in Shibli’s text, and it is for this reason that her text needed to be silenced, for it now speaks of the present and cannot be made into a museumized archived narrative; it cannot be made to be about the Palestinian as the iconized indigenous, for what was willed to be seen as the raped murdered victim, has risen as a fighter, confronting a colonialist project that fails time after time in hiding its colonial face. Shibli’s text itself is a movement backwards, a movement that brings back to the fore the colonial military base as a point of origin of the ‘socialist’ Kibbutz, which is an integral part of a colonialist project based on uprooting, plunder and murder, all beautified with words about humanity and ethics. This is not all, Shibli’s text is also about the continuous presence and resistance of the Palestinian, the Palestinian as life and land; in that too, the text transgresses the limits of legitimacy, even those of literary legitimacy.